It can be tricky to keep track of what your characters know, what the reader knows, and what information needs to be given to who by who at what point in the story.

I love a bit of dramatic irony. Any time I can show the reader that the character is going into a situation without all of the information they need, that makes me happy deep in my slightly evil writer's soul. One character witnesses a thing that means the other character's plans are doomed to fail unless the last minute message can get through? Sign. Me. Up.

|

| She knows! But she doesn't know that he knows she knows! (c) NBC/Bryan Fuller |

But it's hard to pull those moments off in prose. (It's a lot easier in visual media, where there's inevitably a certain amount going on in any given frame that the viewer knows and the characters don't.)

There's plenty of writerly advice about exposition and how not to do it - google 'infodump' and 'as you know bob' for some perennial favourites. But here are three examples that have been bugging me recently.

I can't tell you that. Why not? Er...

Jake knows that Terry loves yoghurt. Jake finds out that yoghurt is going to be banned in the state of New York, but doesn't tell Terry. Even when Terry mentions how happy he is that he'll always be able to buy yoghurt, Jake doesn't say anything.

How does that make the reader feel about Jake?

|

| Pretty much like this (c) Brooklyn Nine Nine |

If you want a character to withhold information, they had better have a really good reason for doing that, and most importantly, you had better communicate that to the reader somehow. They don't need to know all the details, but they have to be able to pick up on the subtext that's stopping Jake giving his friend the information that he needs.

Perhaps Terry says something like 'man, if anyone told me I couldn't have yoghurt any more, I'd break his neck' and Jake replies 'no doubt no doubt' and then runs out of the room - Jake is still a bad friend, but it's because he's a coward, which is understandable even if it's not likeable.

Whereas if you don't put in some kind of acknowledgement, it just seems like you either forgot that Jake had that information, or - which is worse - decided that he couldn't say anything because you want Terry not to know it until later, and hoped nobody would notice.

Yoghurt aside, this tends to apply especially to secondary characters who are supposed to be wise or in positions of power, your kings and wizards. If they have vital information about how to defeat the dark lord, you might want to consider having them tell somebody about it - perhaps this hero who has come riding by, asking for dark lord defeating tips? If they keep schtum and then rock up at the hero's darkest hour saying 'by the way, the dark lord's weakness is his little finger - I knew that all along, just needed to double check you were worthy before I told you', you might have a small plot problem.

I've just seen a unicorn, but never mind that - what's for lunch?

Whether it's urban, space, epic or nostalgic, pretty much all fantasy writers have to deal with how their character reacts when they come across something that doesn't fit into their understanding of the world.

Sometimes, there's no time to dwell - they're in the adventure now, and there's no turning back. Protagonists like Alice can take Wonderland in their stride, because they've crossed the threshold into another world, and no amount of logic will change the fact that you've eaten a cake and now you're huge and being poked with a stick by a toad in a waistcoat.

|

| 'Seriously, which part of this would you like me to question first?' (C) Carroll/Tenniel |

But sometimes you want to present your hero with a little teaser of the weirdness to come, or you need your protagonist to go on living their normal life around the developing strangeness. When it's handled poorly, you can get situations where the character gets a mystical vision, or is briefly transported to another world, or sees a unicorn cantering down the high street... and goes on as if nothing strange has happened at all.

There are ways around it, and I've used some of them, and not always the particularly clever ones either. People are very good at disbelieving the evidence of their own eyes, you just have to make sure they're doing it for a reason that makes sense. Perhaps Will already has incredibly vivid dreams, or terrible insomnia (or is taking some kind of substance if it's not a children's book). Maybe Ruth knows that as a teenage girl in Salem, admitting to anyone that she did magic in the woods last night is not a good survival plan. Maybe Meg just doesn't have anyone in her life she would

want to tell that she turned into a fox...

One book that I think handles this brilliantly is Paul Cornell's

London Falling - four different characters have weirdness thrust upon them, and they each handle it differently, each one relating it to their specific character traits and experiences. Having a group of protagonists whose experiences illuminate their similarities and differences, who can confide and check in with each other about what's happening is a genius move.

Walkers, Walkers everywhere and not a brain to eat

This is where the Z word comes into it.

There's a whole TV Tropes page about this one.

The problem with 'genre' fiction is that about 5 times out of 10, the reader knows roughly what to expect from the plot before the characters do.

Even if a zombie story manages to convince you that it's set in a world that's exactly like ours except that none of the characters know what a zombie is,

you still know exactly what's going on. The heroes can't help it, but they

will seem slow on the uptake if it takes them a long time to figure out that the strangely dead-looking people shuffling towards them with grasping hands and drooling lips are undead, hungry and not just looking for a hug.

|

| A classic exception to the rule - Shaun of the Dead plays this trope for laughs and pulls it off magnificently. (C) Simon Pegg/Edgar Wright |

Look at your book. It doesn't matter whether it's finished and sold to a publisher or not, think of it as a publishable object for a minute. Imagine your ideal cover. Now imagine your worst nightmare cover, because let's be honest, it's best to be prepared.

Is there a 98% chance your book is going to have a bloody great dragon on the cover? Is your blurb inevitably going to include a phrase like 'But when Sophia's uncle is kidnapped by fairies, she must...'? When readers pick up your book, do they already know that there's going to be magic going on inside, and do they have a pretty good idea of how that magic operates?

If they do, that's not necessarily a bad thing. After all, if you say there is a dragon, the reader might not know exactly how

your dragons function in

your world but they'll have an instant thumbnail idea of what you're talking about, which means you can either save on the expositional legwork or get your subversion on.

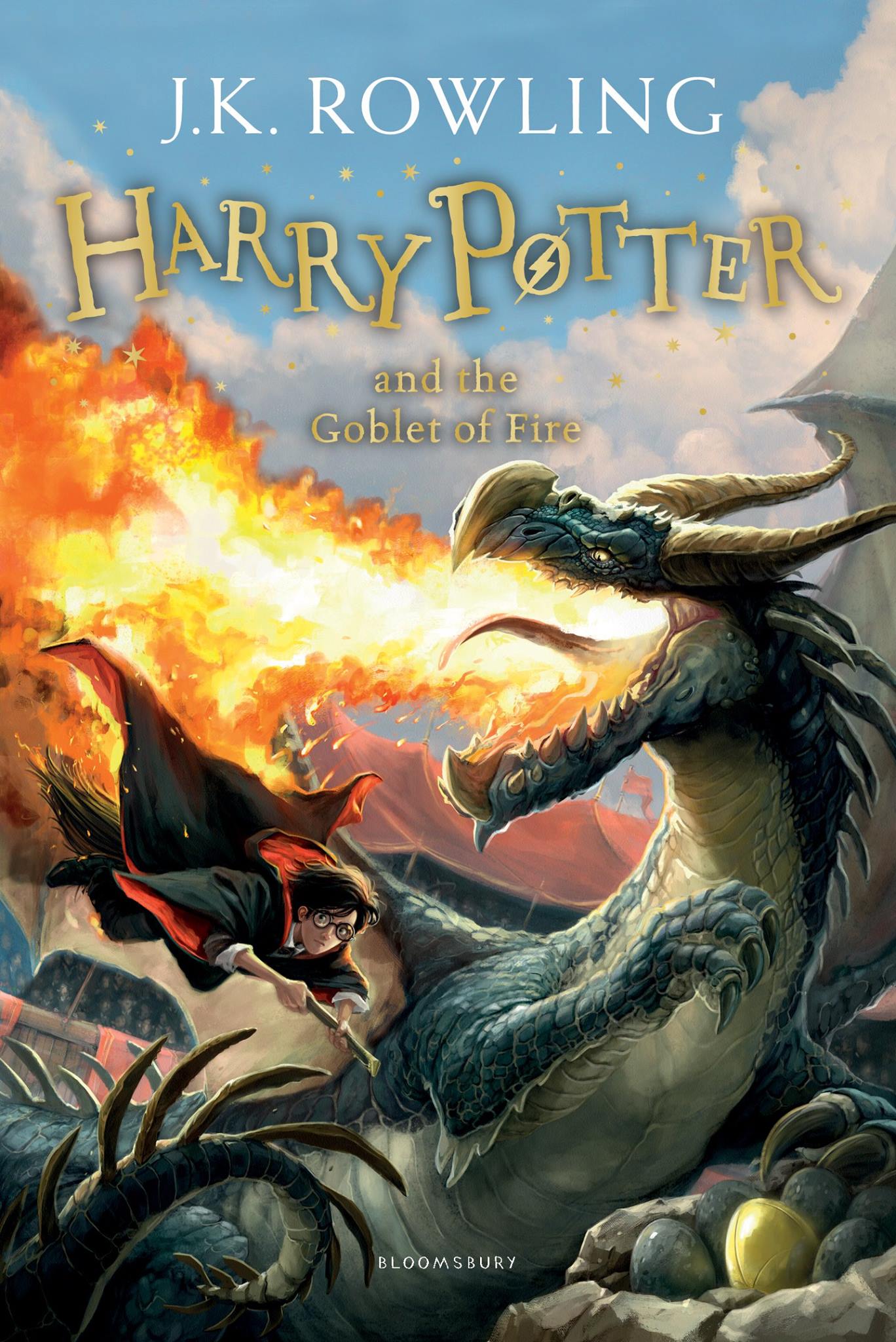

The first Triwizard task is a secret and a mystery! I wonder what it could possibly be! (c) JK Rowling, awesome cover art by Kazu Kibuishi, Jonny Duddle and Giles Greenfield respectively

But, it does mean there's not much point trying to go for the 'surprise' magic reveal late on in the book (which, to be fair, JK Rowling doesn't - it's not really a surprise

that there are dragons, because there have been dragons in the series before, it's finding out

when Harry's going to encounter one that is the fun part). There's pacing out your story so the character isn't given more than she can handle, and then there's dragging things out so much that the reader loses patience with the story.

Suspension of disbelief is for things, not people.

That's probably a debatable statement, but for me, a book can succeed or completely fail on whether I believe that the characters would act the way they do. You can throw as many plot twists and fantasy elements at them as you like, but if Jake doesn't mention the yoghurt ban, you're in real trouble!